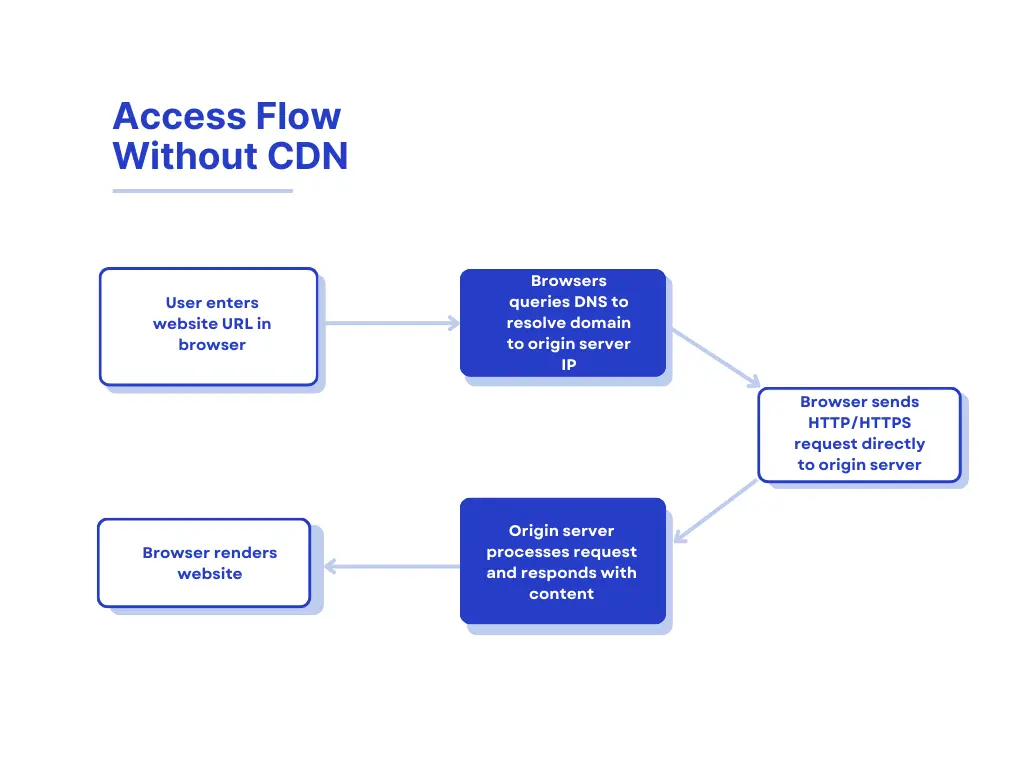

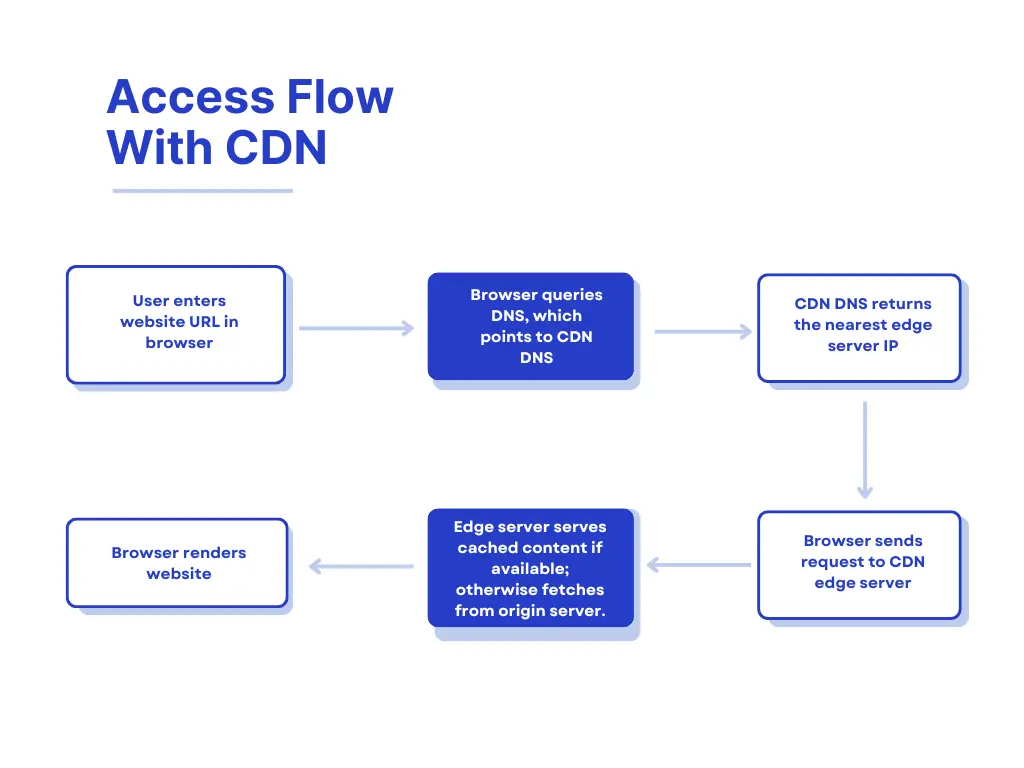

Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) are a core part of modern internet infrastructure, enabling fast, stable, and secure online services. A CDN is a distributed network of servers designed to deliver web content to users more efficiently based on their geographic location.

At the same time, reports from major CDN providers such as Cloudflare and Akamai, along with public threat intelligence and law enforcement investigations, confirm that CDNs are increasingly abused for phishing, malware distribution, and command-and-control activity. From a CDN forensics perspective, understanding this abuse does not weaken the value of CDN technology—it strengthens risk awareness and investigative capability.